Haa Shuka

Alaskan Native Arts

Haa Shuka, translated from Tlingit to English, means

“Everything we have ever been, everything we are right now,

and everything we are going to become.” (Leer)

I know I am a guest on this land that I call home. I can feel the ancestors of all those who came before to this beautiful wild country; I can feel them in the moose, bear, and beaver in the water as it flows in the Chena River through the middle of Fairbanks. It’s in the fireweed that tells us summer is here and when it is ending. It’s in the wild blueberries we pick in the fall and the 40-below air that stings our faces in the winter. It’s in the Native Alaskan Art that is passed down from generation to generation. It’s not just a craft but a history, a story of who, why, and where they came from. It is Haa Shuka.

The Native Alaskans teach that creating art connects you to your past. In preserving their craft, they bond with the past generations and connect with future generations. The designs, the weaving, the baskets, the totem Poles, and the beading shows that each work of art is a history lesson.

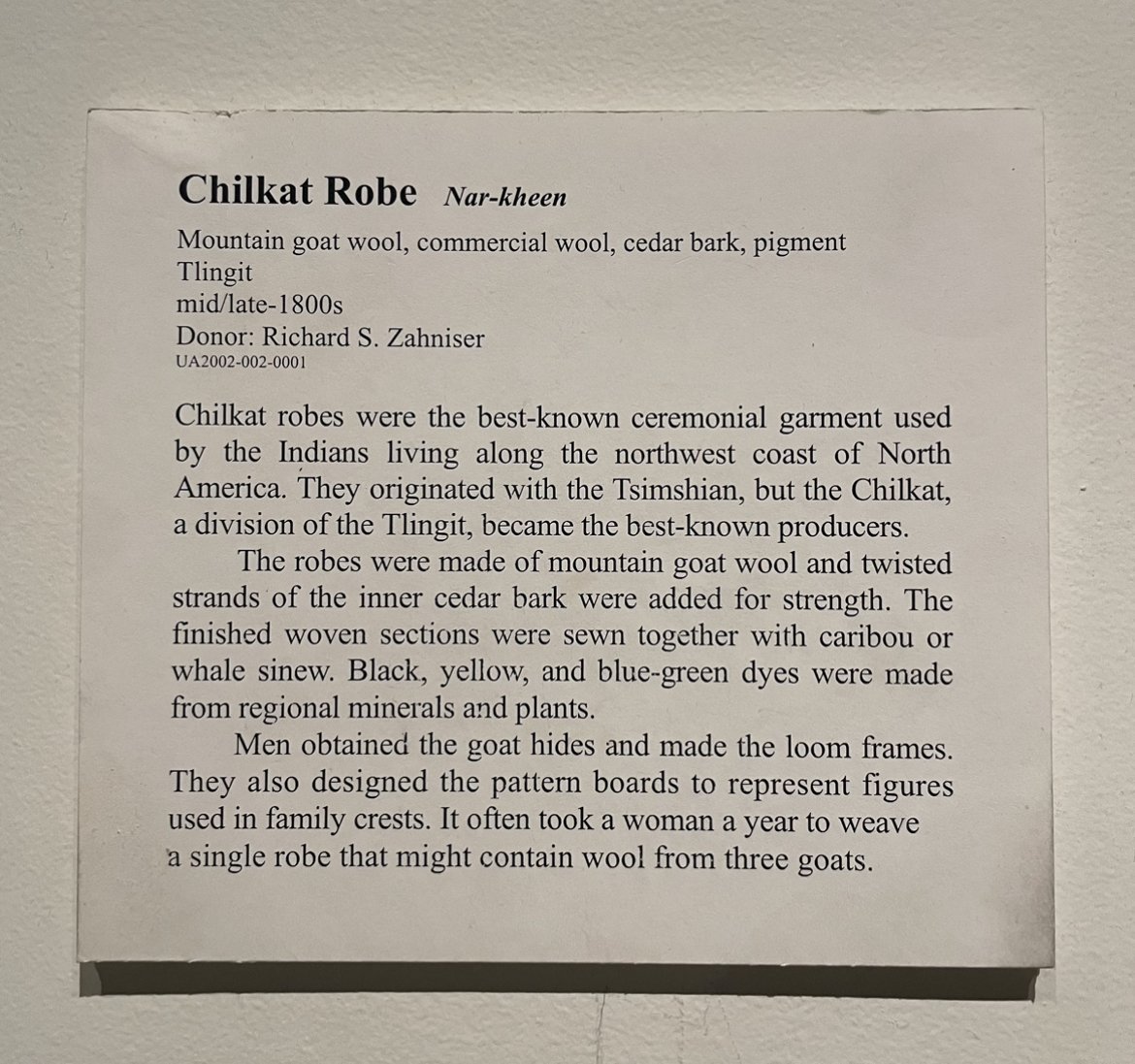

Blanket Weaving

Clarizza Rizal 1956-2016

“This is a spiritual practice for women.

When you raise up the spiritual practice of women,

you raise up the level of harmonious existence.”

Clarissa was born in Juneau, Alaska, in 1956. She was a highly respected cultural leader and a multi-talented artist who contributed to the revival and perpetuation of Chilkat and Ravenstail ceremonial blanket weaving. She educated scores of students in Chilkat, Ravenstail, and button robe techniques. (Pich)

Clarissa has designed and created more than 60 Chilkat, Ravenstail, and button Blanket Robes. (Esterle) She received many awards during her lifetime, including in 2016, The National Endowment for the Arts.

These difficult and time-consuming twined robes made of wool and cedar bark depict highly stylized images of the crests, which embody a clan’s history and eminence. In the gender-divided world of Tlingit art, a Chilkat robe is the female equivalent of the male-carved totem pole.

Clarissa said one of these robes could take up to a year to create. It is said by weavers to be one of the most complex styles in the world. They are beautiful with their traditional colors of lemon yellow and robin egg blue, outlined in the bold black border. The beauty of the Chilkat blanket is not only graphically stunning, but one must feel wrapped in history and love when wearing it.

Beaded Headress

Beaded Headdress

Culture: Sugpiaq (Alutiiq)

Region: Alaska Peninsula

Village: Ugashik

1884

In my studies of Native Alaskan Art, I kept returning to this beautiful Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) Beaded Headress I read about in my Indigenous Cultures of Alaska class (Langdon, 2014, 51). The Sugpiag (Alutiiq) women would wear these intricately beaded headdresses for essential ceremonies, festivals, and celebrations. These headdresses were made from hundreds of glass beads strung on sinew. The beads were strung into a tight-fitting cap with dangling long strings that dangled on the sides and down the back. The longer the trails down the back, the higher the social position of the young lady. (Langdon, 2014, 51) The chief’s daughters’ headdresses would extend far down their bodies, sometimes reaching down to their heels. (Simeonoff, n.d.)

The Alutiiq people have been beading for thousands of years. The earliest beads were made from shells, bones, ivory, amber, coal, shale, slate, small stones with ancient drawings, and even fish vertebrae. Russian traders in the late 18th century brought over glass beads, and the Alutiiq people started using these glass beads to make headdresses and jewelry. (Beading, n.d.).

Every Headdress is unique, and no two designs are alike. (Lincoln, 2022) The Beaded Headress pictured above comes from the Ugashik Village on the Alaska Peninsula. The National Museum of Natural History acquired this piece from William J. Fisher, a naturalist and collector of Alaskan Artifacts in 1884. The headdress has a cap of small to medium beads and a long tail of heavier beads that widen at the bottom and is 51 cm long. The hundreds of glass-colored beads in red, white, green, and black represent the traditional Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) style. (Arctic Studies, n.d.) Whoever wore this headdress must have felt incredibly celebrated.

The Tradition Continues

Beaded Dentalium Shell Headdress

Christalina Jager

Date: 2022

Medium: a variety of colored beads and dentalium shells.

Culture: Sugpiaq (Alutiiq)

Location: Port Graham, Alaska

Chugachmiut Heritage Preservation, Paluwik

The color pallet in this headdress is beautiful. Getting the round shape for the head with the design must take hours. It is breathtaking. I would love to own one of these headdresses.

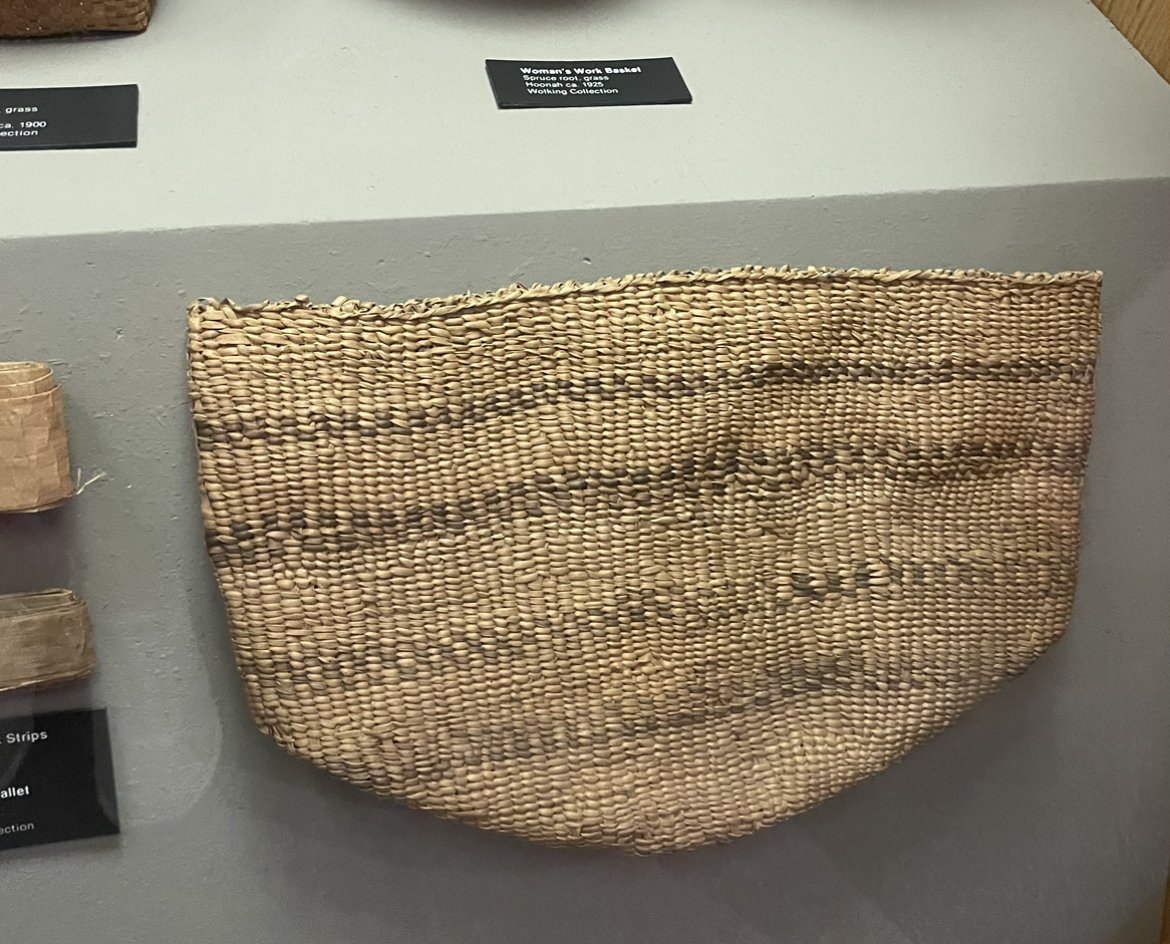

Basket Weaving

Object name: Grass bag

Alaska Native object name: ukilqag "grass bag with wide-open mesh"

Language of object name: Cup'ig

Culture: Cup'ig (Yup'ik)

Region: Nunivak Island, Alaska

Village: Mekoryuk

The Yup’ik children are taught the importance of the land and using what’s around them for survival. They are taught the difference between tundra grass and beach grass, Tundra grass is cylindrical in shape and hollow inside. It breaks easily when dry. The beach grass has a blade-like shape, high tensile strength, and is flexible when dry. The beach grass is gathered after the first frost in the fall or in the summer after it is mature.

Grass harvesting, processing, and weaving takes expert knowledge and great skill. Different weaving techniques and designs were used to make grass bags and baskets for harvesting, carrying, processing, storing, and cooking food, which were essential to the survival and success of a family and community. A grass carrying-bag like this is called an ukilqag (grass bag with wide-open mesh) in the Cup’ig language spoken on Nunivak Island, Alaska, and called an issran (grass carrying-bag) in Yugtun, the Yup'ik language spoken in Southwest Alaska. This type of grass bag would be used while harvesting grass and plant foods because once a plant is picked, it begins to spoil. Weavers knew that air circulation would help picked foods stay fresh while a person was out gathering, so they designed grass bags with gaps in the weaving, a technique called open-weave twining. (Gainsbourg)

Next on my bucket list while I am here in Alaska is to learn how to do this basket weaving. They are so beautiful. Definitely a work of art. The Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center on the Alaska Channel did an amazing documentary on Yup’ik tradition of weaving an issran.

Beading

Donna Cole

@Joyful Alaskan

Object name: Rose Box

Medium: Beading on Birch Wood Box

Culture: Athabaskan

Region: Fairbanks, Alaska

I contacted my friend, local Fairbanks artist Donna Cole and asked her if she could tell me a bit about her Athabaskan Beading tradition. The following is what she sent me.

I took up beading when I was a teenager living in the village of Manley. I was initially taught by Sally Hudson, an Athabascan elder. Beading just has a fascination for me and is a way to reflect the beauty of my surroundings. I can always appreciate and take inspiration from other beaders, both past and present.

It also has a tradition in Athabascan culture as a peaceful/joyful activity. Most elders say not to bead while you are in a bad mood, as that will affect the work. This is especially important as, traditionally, beadwork was made to give as a gift, and when you give a gift, it should be made in an atmosphere of peace and joy so that those feelings will accompany the piece of work and transfer to the intended receiver.

I love Donna’s work. The one above has so much love and feeling. It encompasses Alaska with the beautiful birchwood box as a background to her beading of the Alaska wild rose. The shading and colors of the beads bring the rose a three-dimensional look. I have tried beading; it is a craft that takes patience and love.

You can follow Donna and purchase her beading on Facebook @JoyfulAlaskan. Here are a few more examples of her work.

University of Alaska Museum of the North

https://www.uaf.edu/museum

If you would like to explore more of Alaska Native Art, please visit the University of Alaska Museum of the North. They have an amazing collection of beautiful Native Art.

“In Ancient Visions, there are creations made by Alaska Natives as long as 2000 years ago. Native Art, Native Worlds, works made by Alaska Natives since the nineteenth century until the present for use in their own communities, occupies the center of the gallery.”

I went this weekend with my boy Sterling. He loves history, and going to the museum is one of his favorite activities. Here are some of the amazing Alaskan art we saw on our visit. There is so much more on display and many mediums I did not cover on my blog today. The Museum of the North’s collection is Haa Shuka.

Works Cited

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aNADxHHCnPU.